Click here for a full transcript

Lyme disease is confusing. A lot of people don’t know what it is or what it can do to you, or how Lyme disease gets in to you in the first place.

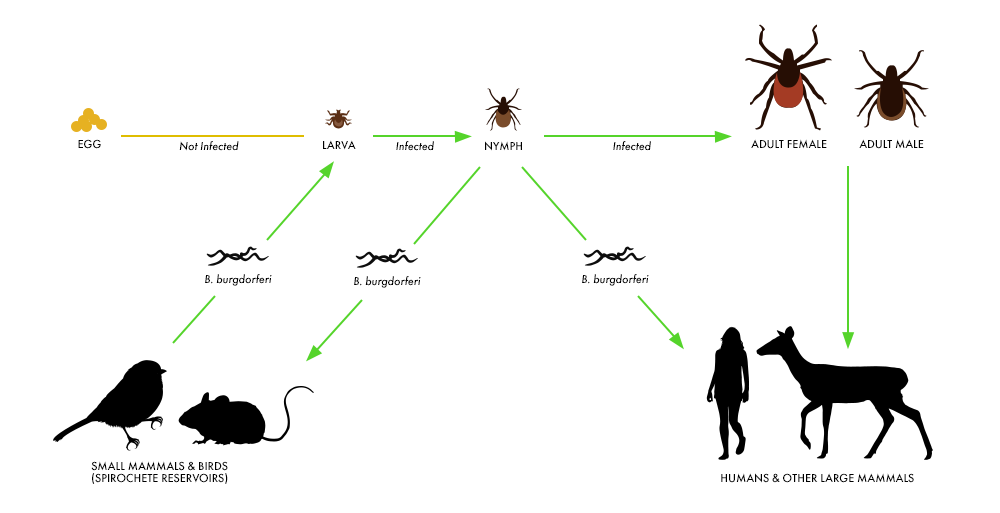

After hatching, ticks need a blood meal at each stage of life in order to survive. Common hosts for tick larvae are small rodents & birds. Bacteria picked up at the larval stage from the primary host can be passed on to later hosts at the nymph - the highest risk to humans - and adult stages. (Sara Plourde, NHPR)

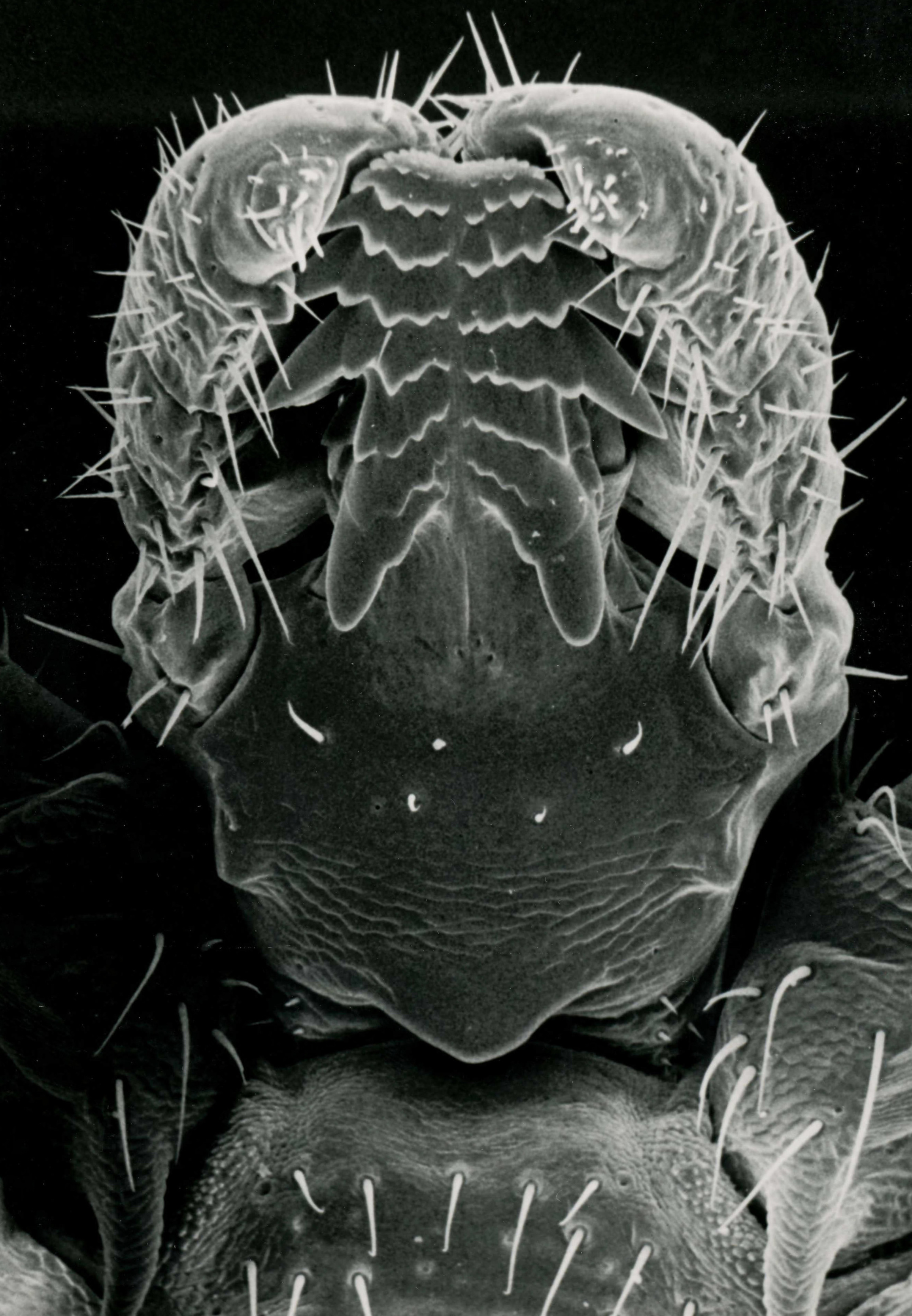

Let’s start with the humble blacklegged tick. Unlike insects, which have three body parts - the thorax, abdomen, and head - the black legged tick has a tear shaped body and... a thing on top. It’s not a face. It has no eyes; it’s totally blind. Scientists call it by a very gross and very memorable name: the mouthparts. These are the bits that work their way into your skin.

On the outside are the palps, which feel around for a good spot to bite. In between them are two sawed blades that rub themselves into the skin, and then flex backwards, pulling the most important part - a spiky tube - into your body.

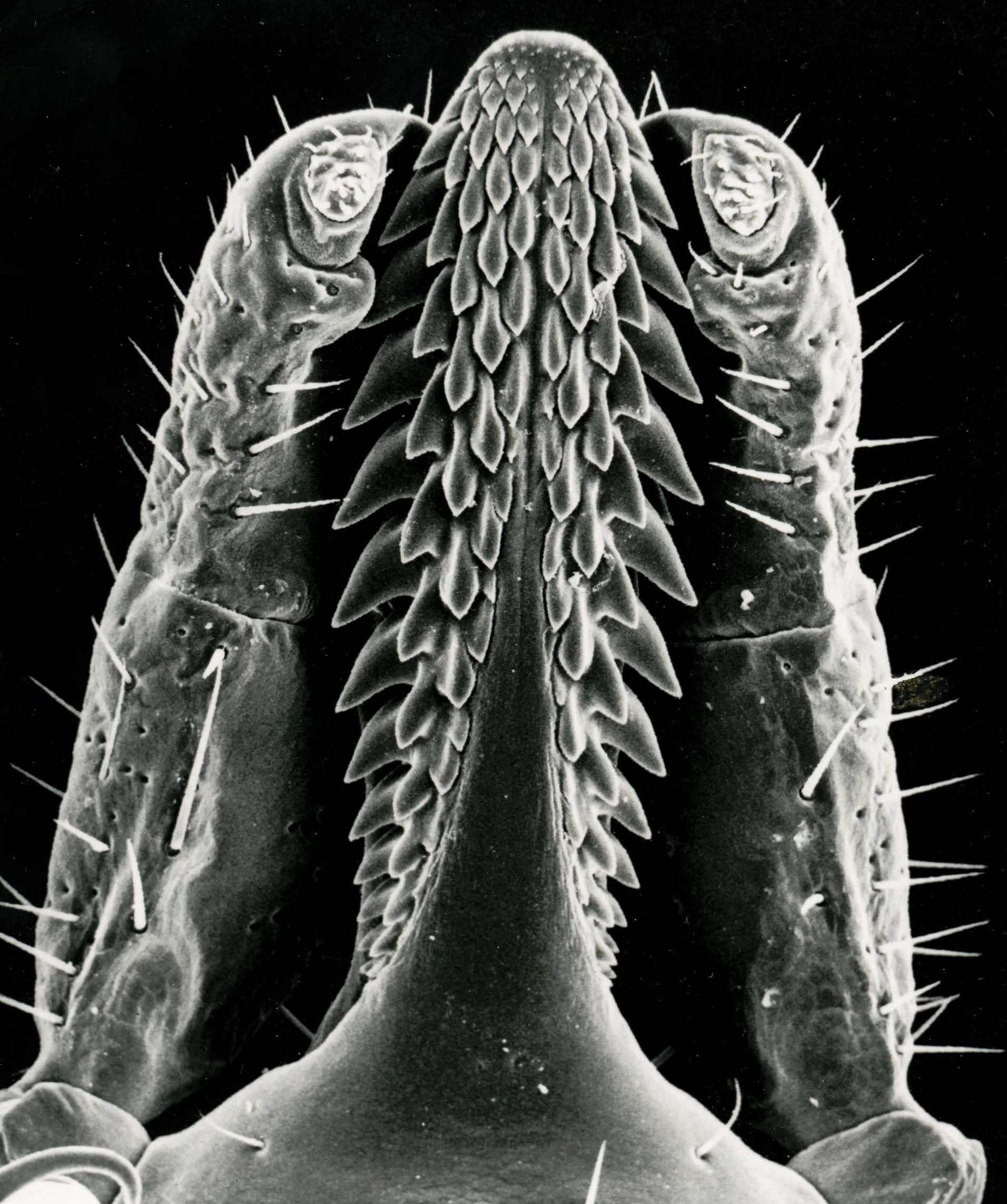

Above: Images taken of ticks under a microscope (Willy Burgdorfer Archives)

That tube has backward facing barbs, sort of like a harpoon - so that once it’s embedded inside the skin, the tick can start secreting special chemicals through it like a straw to help prepare its meal.

(Sara Plourde, NHPR)

In the first 24 hours, ticks are not feeding on you. They are injecting you with antihistamines so you don’t get a welt that might tip you off to the fact that you have a tick inside you; with anticoagulants so your blood doesn’t clot; and with cementing agents that literally bond the tick’s mouthparts to the body. They are doing all of these things to cover their tracks, so you don’t know you’ve been bitten.

Once they’re done doing all of this - numbing you, gluing to you, medicating you - they start to drink in earnest. But they aren’t just drinking blood. They are also secreting saliva into your bloodstream. It’s the spit that the Lyme pathogen - Borrelia burgdorferi - uses to travel into your body

You won’t contract Lyme disease the second the tick burrows into your skin. Some refer to this as the “24 to 48 hour rule.” After the tick has done its meal prep, it starts drinking blood, which gives the tick and the bacteria a food source. The bacteria needs that food source to grow and multiply, so it takes time. The amount of time that takes is controversial - there are anecdotal stories of people who get Lyme after being bit just a few hours earlier - so 24 - 48 hours is more of a guideline than a hard and fast rule.

Borrelia spirochetes within the midgut of a tick (Willy Burgdorfer Archives)

The pathogen that causes Lyme, the spirochete, is a single celled organism shaped a little bit like a snake or a corkscrew. And it’s covered in textured spikes known as Outer Surface Proteins. Different strains of Borrelia have different protein structures, which is the reason that you can get Lyme disease more than once.

Many of the symptoms that people with Lyme experience come from the immune system trying to fight off infection, including the characteristic bullseye rash.

In a best case scenario, the disease is found and the doctor orders a round of antibiotics that doesn’t kill the bacteria but sabotages its production and stops it from multiplying.

If you’re one of the thousands who don’t get diagnosed, though, that little bacteria can outrun your immune response and lodge itself in your joints, in your brain, in your cells and start to do some real damage.

The worst case scenario…is coming in episode 4.