Click here for a full transcript

Editor's Note: A previous version of this story identified Mary Curtain Pierce as a critical care nurse at Alice Peck Day Memorial Hospital at the time of her illness in 2016. This is incorrect. She was working at a different hospital in New Hampshire at that time. We apologize for the error.

Sometimes, it seems like there is a gulf between epidemiologists and health care providers, and the actual patients they’re trying to help. Two people, looking at the same information, and walking away with radically different conclusions.

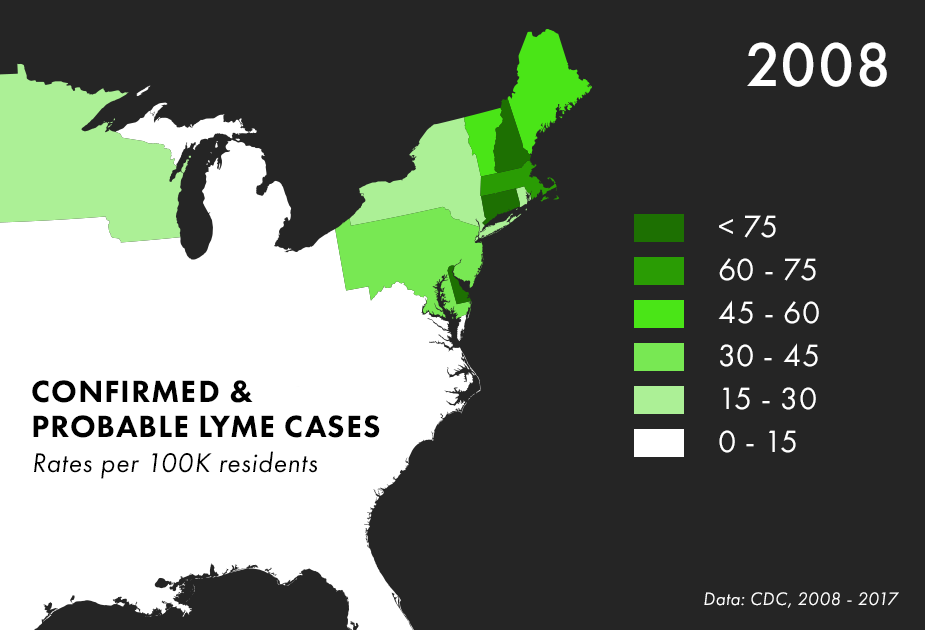

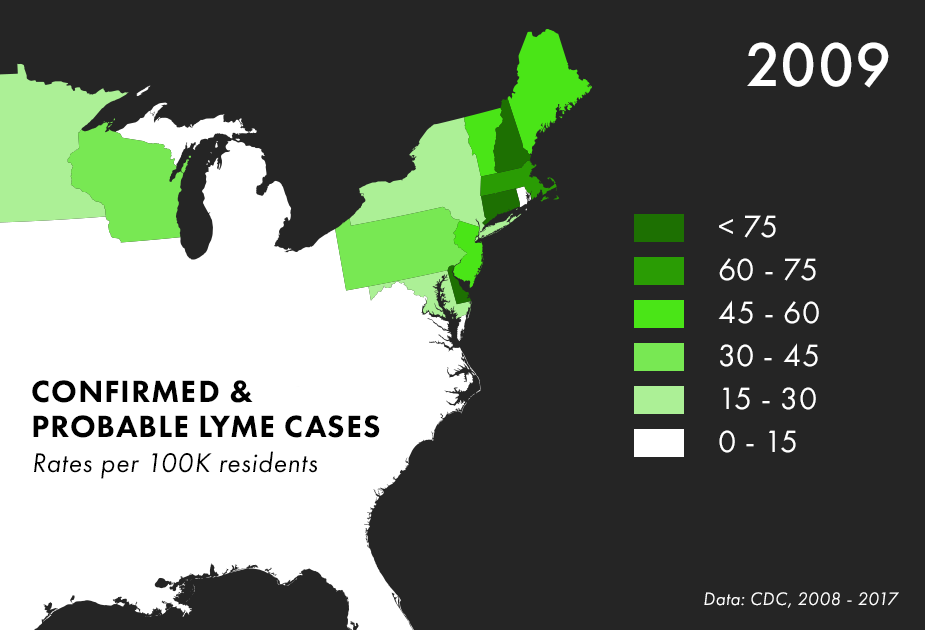

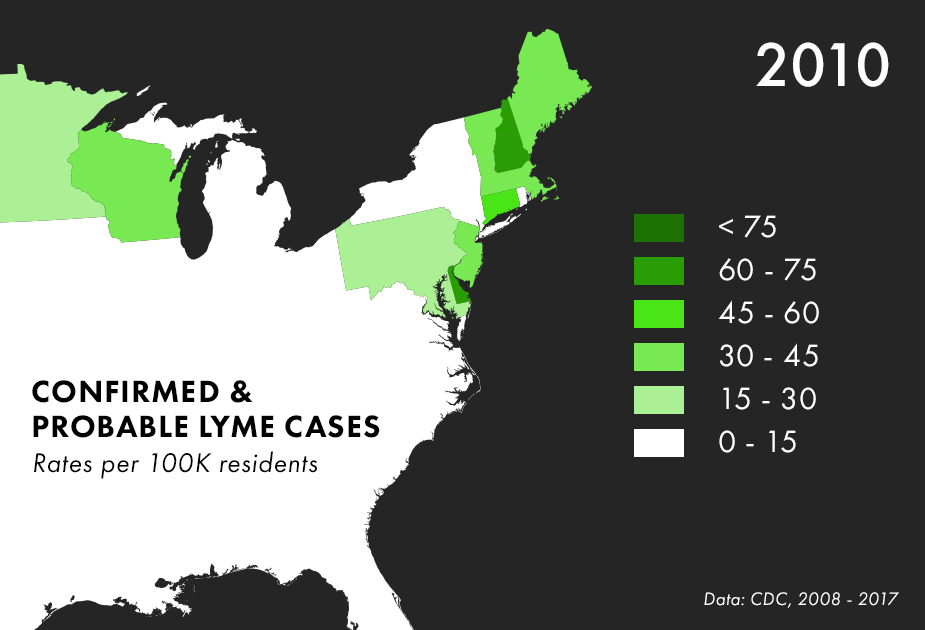

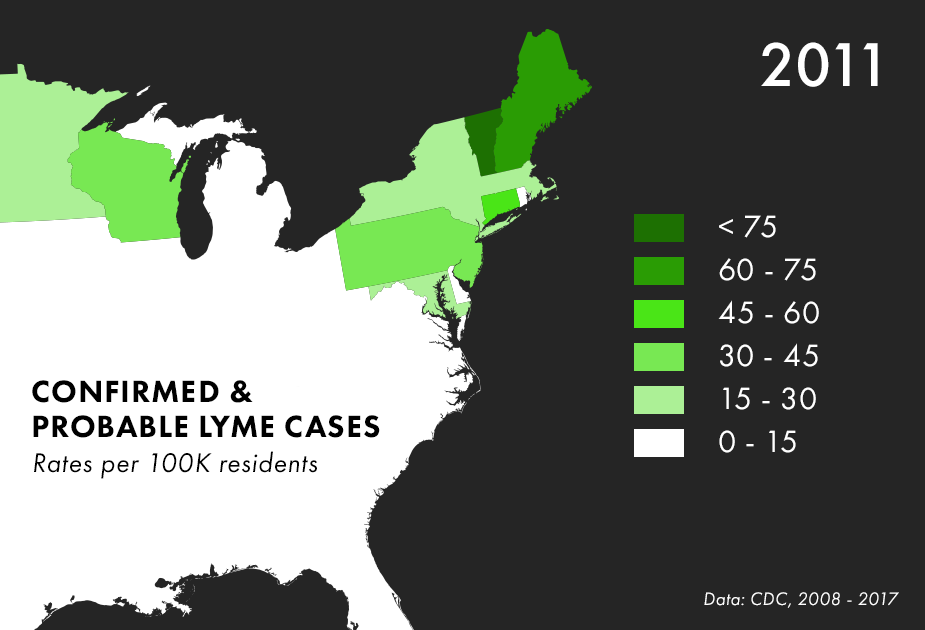

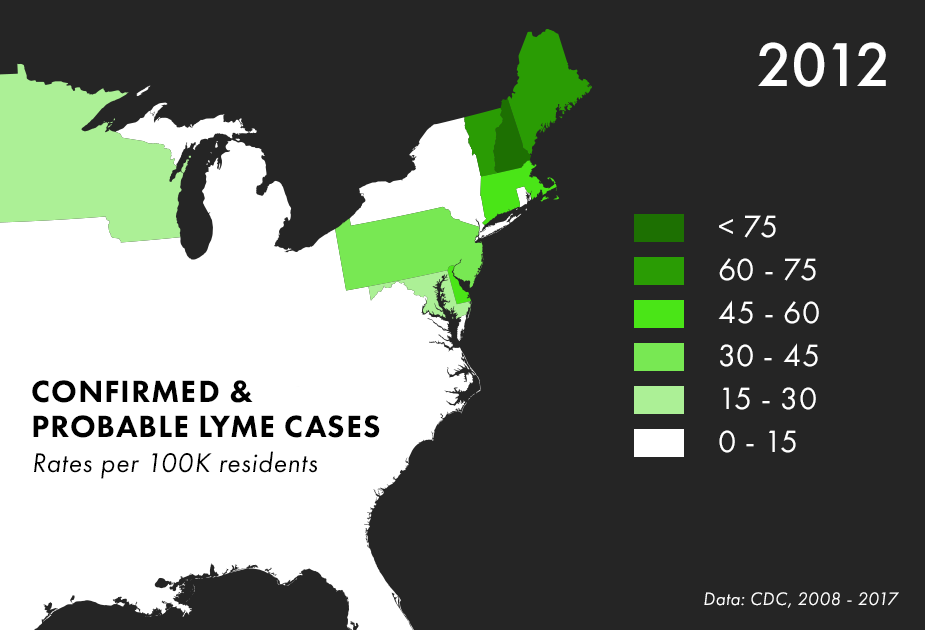

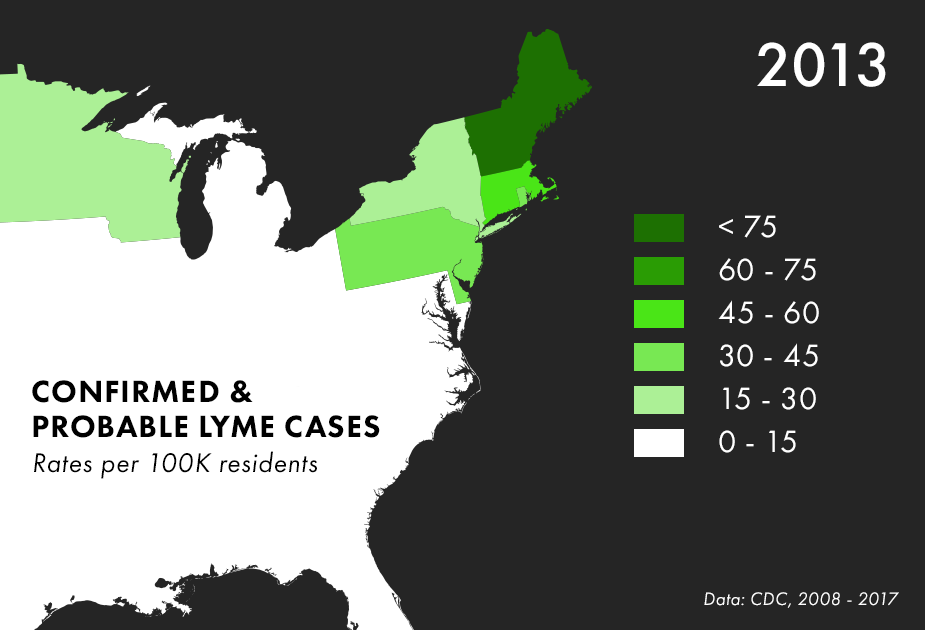

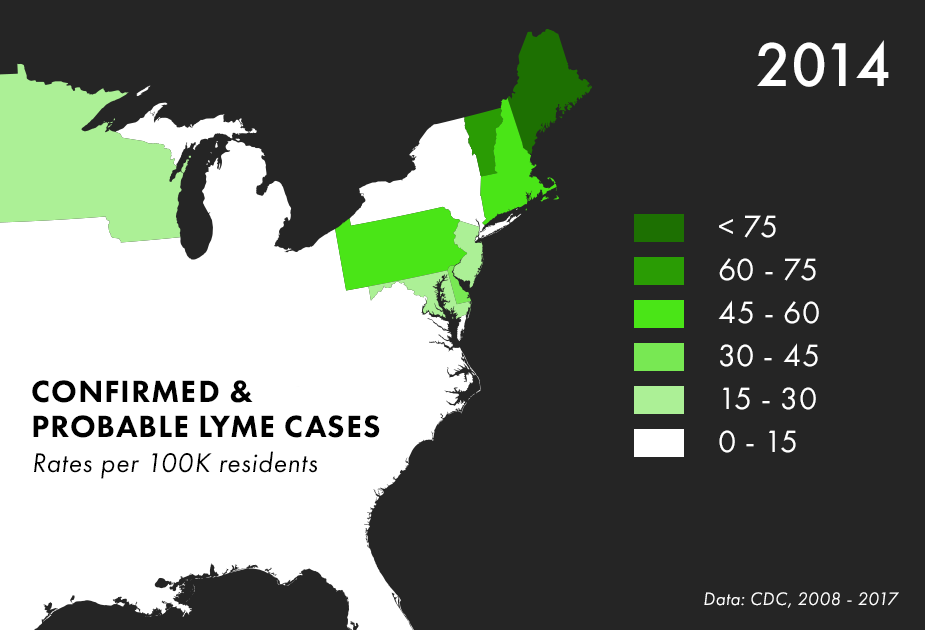

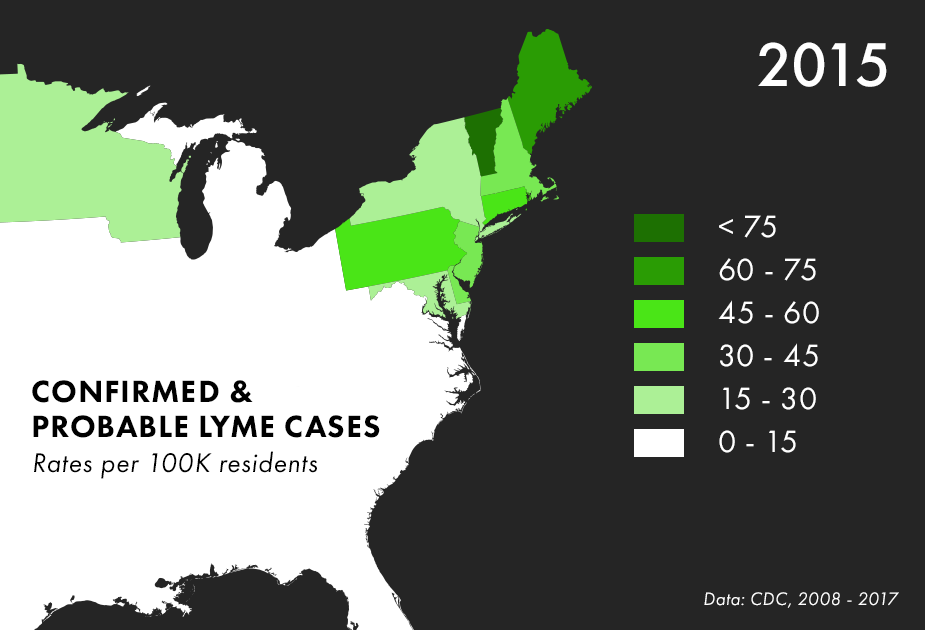

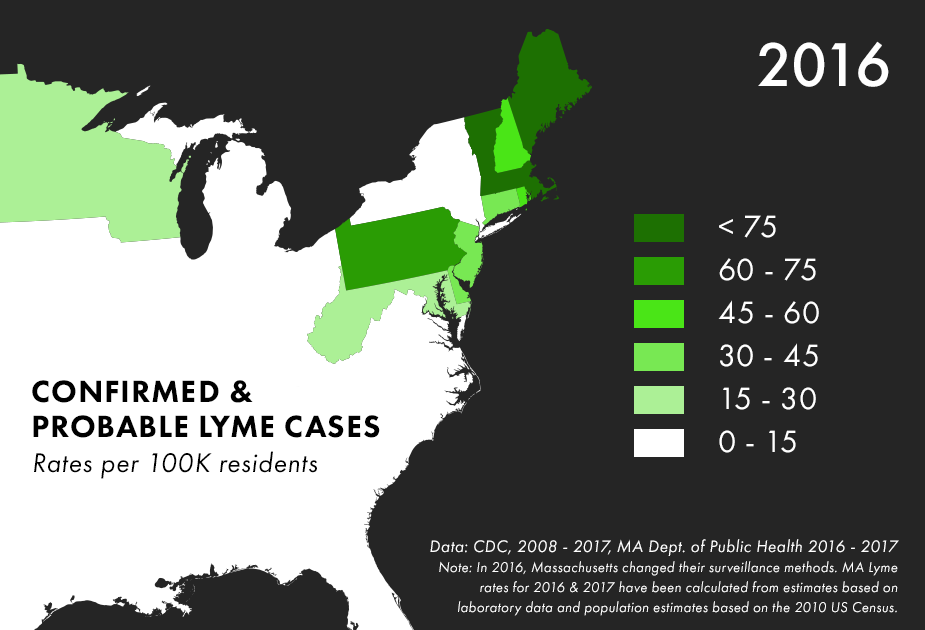

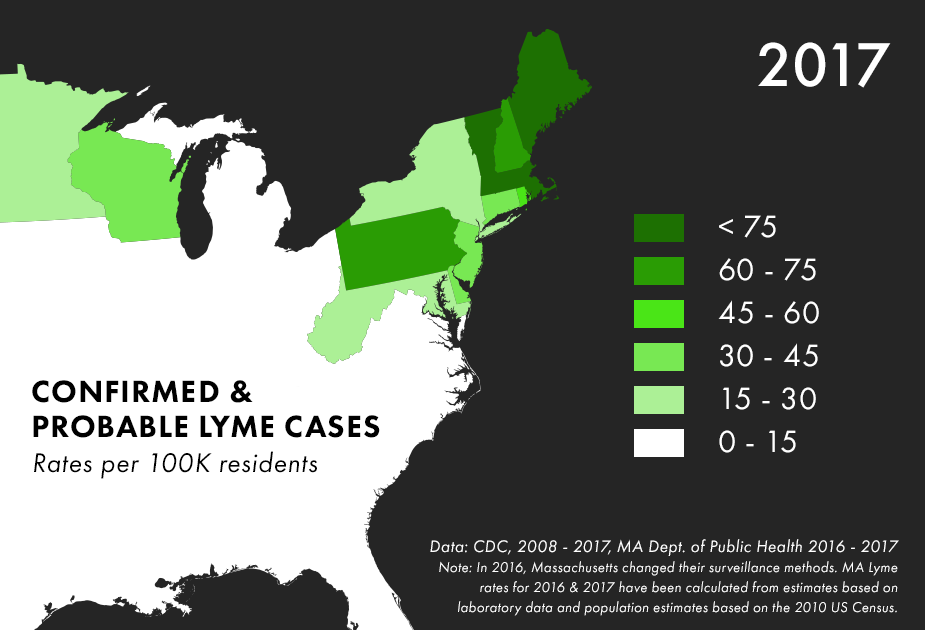

Note: There are many complications to collecting Lyme data, and the maps above represent only the best data we have available, not all possible cases of Lyme. For more on the process behind and limitations of Lyme disease surveillance, read this documentation from the CDC.

Chronic Lyme is the central controversy of Lymeworld. But what is it? Where does it come from? And why is treating it, with long rounds of antibiotics, so controversial?

According to the experts that help set treatment guidelines, 14 days of doxycycline, a standard oral antibiotic, is supposed to cure most cases of non-complicated Lyme disease. New draft guidelines suggest even less - just 10 days. But some people don’t feel all the way better after treatment for Lyme disease. In 10 to 20% of Lyme cases, patients continue to have arthritis, or pain and fatigue, or cognitive problems.

For people who have a clear diagnosis of Lyme in the first place, authorities call these cases Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome. There is no CDC-official name for ambiguous cases, with weird symptoms, and unclear lab results, but many of these patients wind up calling it Chronic Lyme Disease.

There are a few theories about why people have persistent symptoms after treatment. The bacteria may have caused permanent damage to the joints, or triggered an auto-immune reaction that lasts even after the infection is treated. The chronic Lyme community have embraced another theory for their lingering symptoms: that the spirochete isn’t actually dead.

According to mainstream medical guidelines on Lyme, the toughest cases - hospitalized patients with Lyme carditis, or cases of Lyme-related meningitis - might require up to 28 days of IV antibiotics. Occasionally, if clear signs of infection re-emerge, another round of antibiotics might be warranted. And yet, more antibiotics are often what chronic Lyme patients end up getting.

When you’re covering Lyme disease, you’ll often hear people say something like:

When will people realize that chronic Lyme disease is a real disease?

But what is it that makes a disease “real?”

For patients, chronic symptoms are very real indeed. But how epidemiologists name and define disease is a moving target, and they argue that chronic Lyme might not be the best way to describe what people are experiencing. Lyme disease, for instance, used to be called Lyme arthritis. The name changed as more was learned about the disease.

Scientists and researchers are wary of the term chronic Lyme because it’s so ambiguous. The symptoms are so all over the place that it might turn out to be lots of different diseases and conditions that have accidentally been lumped into one.

Regardless of what we may discover in the future, in the present, patients with chronic Lyme and Post-Treatment Lyme are subjecting themselves to repeated rounds of long-term antibiotics, in some cases intravenously.

Antibiotics are serious drugs. Infectious disease experts are so alarmed by unnecessary or ambiguous antibiotic therapy because thousands of people die every year from infections acquired during treatments that aren’t actually helping.

And then there’s the possibility that hundreds of thousands of people will die because antibiotics won’t work anymore. Antibiotics are the only class of drugs that lose effectiveness over time. It’s like being put in a time machine where patients are dying of infections that a decade ago could have been treated with an antibiotic. Patients who gamble on antibiotics, when there is unclear evidence that they need them, aren’t just risking their own necks but are, in a small indirect way, contributing to antibiotic resistance.

Lyme disease is not the leading cause of antibiotic resistance. Far from it. Colds, bronchitis, and urinary tract infections are the bulk of problems that lead to unnecessary antibiotic use. This also isn’t a straightforward causal relationship. Taking long-term antibiotics does not mean that ten people will die from an infection.

But from a symbolic point of view, Lyme disease does present a particular problem. The treatments are being used despite minimal evidence of benefit and with no clear sense that the therapy will cure patients for lengths of time that are otherwise unheard of in medicine - years. This is why mainstream researchers are skeptical of chronic Lyme.

So this is where we are. Patients and advocates fight for the right to treat with long-term antibiotics. The medical establishment fight to stop the trend from going too far.

The answers aren’t easy. But you do have to hope that everybody is asking the important questions.

Because either way, the stakes are very, very high.

In episode 7, we zoom in to look at the ecological systems that spread Lyme, and zoom out to see how human society has helped to usher in this epidemic.